It’s Monday and I need to write a blog article, but I’ve got a mental blank. My training suggests that this will be resolved by writing, so here we go:

Once upon a time, I met the father of a friend, who made very detailed models of tanks for use in wargames. He was a Major in the Australian Army, and the wargames he was playing were at work. If one of the tanks got ‘killed’ he would take a large hammer out from under the table and smash it to pieces. This was his way of linking consequences to an adverse outcome.

But first, a detour by way of background.

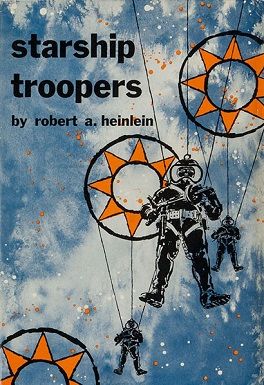

Starship Troopers

In our modern age, ‘Starship Troopers’ has become a parody, or a satire of fascist cultures. I blame Paul Verhoven for this, because, as usual, the film creation has overtaken the book.

A lot of the book resonates with my own experience. Like many of us, I’ve done military recruit training, and since this forms the majority of the book, I felt a lot of it viscerally. When the hero gets a letter from his old teacher after deciding to quit on that long route march, it makes me tear up every time.

In the book, it’s worth noting that the aliens are really a side note, albeit one that implicitly criticises communism. In fact, most of the narrative is social commentary about the responsibility of citizens in a society, with some military stuff thrown in for colour.

Introducing the social narrative

Heinlein reportedly wrote the book explicitly to criticise the thinking of the US government following the cancellation of a nuclear test series in the 1950s – starting the whole trend of using Science Fiction to critique politics.

But the other stream of narrative is how people’s perceptions change during the course of a conflict. A father is resolutely against military service until his wife is killed. A brilliant friend who pursued noncombat roles is killed in an alien attack. A rich and privileged young man becomes aware of the true nature of society.

Our hero’s morale changes noticeably at various points in the narrative in ways that are connected with the broader war.

So, why am I writing about this on a hobby blog? Well, ultimately it’s because I’d like to be able to link the social narrative of the campaign to the context of a played scanario. Particularly, I want to explore how the decisions we make affect the outcomes of the campaign on a level over and above win/lose.

I don’t believe this is often attempted.

Actions and consequences

When developing ACP164, I was struck by how much Albedo considers links between citizens and their society. For example, the comic follows the transition of Erma Felna, EDF from being a decorated war hero to an unknown transient on a planet far from home. More broadly, it deals with the consequences of military action on civilians and military alike. On the whole, it uses the war as a backdrop to the story rather than the narrative.

I wanted to design this relationship into the game, but it’s difficult. How do you incorporate these links into a wargame?

There are several things that I identified, from a macro to micro level.

Victory Points

When I write a campaign setting, I allocate Victory Points (VP) to the outcome of each scenario. Victory points indicate who is winning or losing, but also affect other things. For example, in the Almata Campaign, the HomeGuard alignment depends on relative VP levels. Because the ‘main players’ each have relatively limited forces, AHG support is important.

This encourages careful selection of the next scenario played, as well as strategic play more generally.

Keeping it Real

A lot of the scenarios use what I term ‘Heroic’ Combat patrol. In this mode, individual heroes act like squads. If a hero is killed or captured, they are gone, unlike some ‘grimdark games’ where personalities can be retrieved and shoved into a clone.

This encourages cautious, realistic play and reinforces the consequences.

Fate is on the Cards

The activation cards have a lot of outcomes that focus on morale. If you’re not doing well, running away becomes an increasingly valid option for the troops you command. We’ve also emphasised certain faction characteristics to introduce both variation and uncertainty.

This encourages making smart tactical decisions to avoid impacting troop morale to the extent where the exercise the better part of valour.

Also, unlike most other games I’ve played, it’s entirely possible to play a game in which you don’t actually get a turn. This hasn’t happened to me yet, but the threat is real. (This is Buck Surdu’s innovation, by the way!)

Other options?

One of my most/least favourite games is DVG’s Phantom Leader, which deals with F4 fighter operations in Vietnam.

I’ve played it dozens of times, and only ‘won’ once or twice. This is due to:

- the Rules of Engagement (ROE) seem to kick in just when you seem to be getting ahead of the game,

- the high level of attrition that you face in a high density SAM/AAA environment.

Attrition is covered fairly well in the ACP campaign setting – when you lose a unit, reinforcements can be hard to come by. But it’s worth considering as part of the development of new games. The ”repple depple” should have an effect on unit morale and capability caused by rapid turnover and new faces in the team.

In the Almata Campaign, ROE are concerned with what force levels can be used, rather than political or cultural issues. Often, they aren’t explicitly called out. My justification for this is that the Albedoverse hasn’t developed the strict legal framework used to govern warfare in our timeline. Perhaps in the future, I’ll look at expanding their use.

Finally, the ACP’s concept of Strategic Initiative can be adjusted based on outcomes.

For example, if a previous scenario destroyed a supply cache, the loser’s initiative might be downgraded to reflect the lack of replenishment. Morale modifiers might be applied following the death of a beloved hero, an epic victory or the loss of a cultural site.

So what?

As we’ve been discussing, there are things you can do in the context of a wargame to reflect the effect of the wider environment. But none of them really moves beyond the ‘wargame’ aspect. Maybe that’s why most designers stick to the combat rules and don’t consider the narrative.

This is probably a good thing. At the end, though, do we really want to? There are already plenty of folks who throw their dice around when they are losing, and maybe we don’t want to make that worse. Games are supposed to be fun, after all.

We all develop an affinity for the miniatures and vehicles that we spend hours painting and basing, but perhaps the only real way to feel the visceral loss of defeat is to smash them with a hammer.

0 Comments